INTERPRETATION CENTRE

Texts for Interpretation Centre from Borgonyà Industrial Community.

Mobile devices are available for our visitors.

01

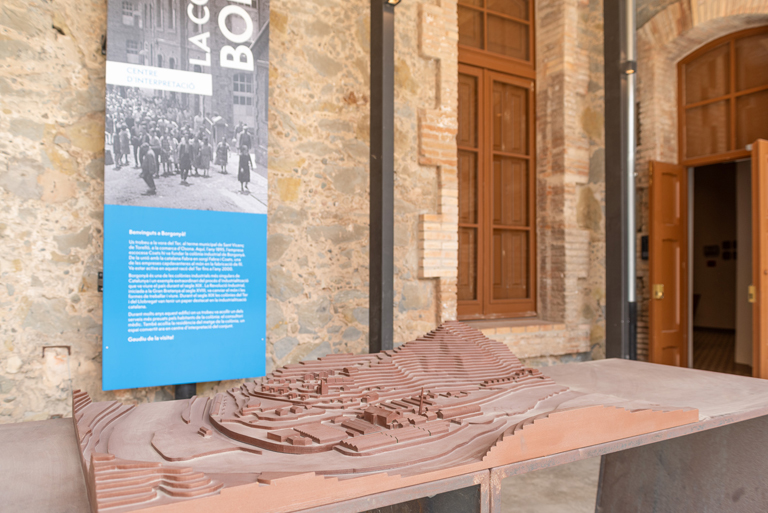

Welcome to the Borgonyà Industrial Community

Welcome to Borgonyà! You are now on the banks of the River Ter, in the municipal area of Sant Vicenç de Torelló, in the county of Osona. Right here, in 1895, the Scottish company Coats founded the industrial community of Borgonyà. Later, the company Fabra i Coats was founded, after it joined forces with one of the leading international thread manufacturing companies, the Fabra company. They were active in this area of the Ter until the year 2000.

Borgonyà is one of the most unique industrial colonies in Catalonia, and it is an extraordinary example of the industrialisation that the country underwent during the 19th century. The Industrial Revolution, which began in Great Britain in the 18th century, changed the world and the ways that people worked and lived. During the 19th century, the industrial settlements of the Ter and the Llobregat took on a significant role in the industrialisation of Catalonia.

For many years, this building where you are now standing, housed one of the most-valued services for the community’s inhabitants: the medical office. It also housed the residence of the settlement's doctor, which has now been converted into an interpretation centre.

We hope you enjoy your visit!

02

A Scottish Settlement on a River of Communities

Industrial communities are highly representative of the industrialisation process in Catalonia, with the two rivers, the Ter and the Llobregat, being essential to their development. The counties of El Bages, El Berguedà, El Baix Llobregat, El Ripollès and Osona were filled with settlement complexes that were functional towns built around a factory, with housing and services for their workers.

The source of the River Ter lies in Ulldeter, in the Pyrenees, at about 2,400 metres above sea level and after some 207 km, it flows into the Mediterranean Sea, near the town of l'Estartit in in the municipality of Torroella de Montgrí. In Osona, the River Ter snakes along a meandering route and changes its initial north-south direction, to take an eastward direction. In the 19th century, the Ter was lined with factories and industrial communities that were to transform the region.

Borgonyà is one of the later communities to be built, however it is also one of the most complete and unique industrial settlements in the entire river basin.

Unique Objects

Time clock

Dey Time Registers Limited brand (Great Britain). Year: 1907. Provenance: The Ter Museum

Punctuality was rigidly enforced in the new industrial society. Work was regulated by strictly- controlled schedules, as shown by this time clock. During the first years of the factory's operation, the working week was established at 64 hours and 30 minutes. However this amount was gradually reduced, and by 1909 it totalled 57 hours and 30 minutes. A working week of 8 hours a day from Monday to Saturday was introduced after La Canadenca Strike of 1919.

EViolations of labour regulations were commonplace in the Ter factories. In Borgonyà, however, working hours were adapted to legislation and sometimes were even below legal requirements. In terms of wages and in comparison with the weekly wages of other factories in the region, Fabra i Coats paid the same - or better - although with fewer working hours. This fact made Hilaturas Fabra i Coats one of the companies with the highest wages per hour of any factory in the Ter basin.

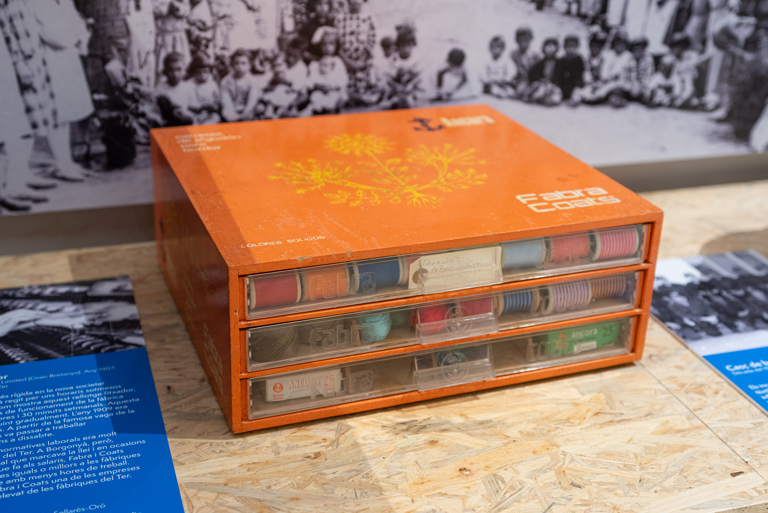

Thread Samples

1960s. Provenance: The Sellarès-Oró Family

Fabra i Coats produced a wide variety of high quality yarns. They were sold under numerous names and were found in every tailor’s store. We were often told by many seamstresses that it was the best thread in the world. Who can say? In all events, the company was certainly a leader in its business sector. Apart from its services to the clothing manufacture industry, Fabra i Coats products were distributed through a large network of retailers, tailors, and haberdasheries, etc., together with an extensive commercial network throughout Spain. In the mid-twentieth century, Fabra i Coats employed 50 sales representatives, each with a company car, supplying some 50,000 accounts.

Fireman’s Helmet

1950s. Provenance: The Ter Museum

Fires were a commonplace hazard in textile factories. Large amounts of fluff and other flammable materials would cause even the smallest spark to ignite fires and spread rapidly. This danger also existed in the industrial community. One of the last fires – and one that is still remembered today – occurred at the end of 1977 in the casino.

Fire prevention and readiness to fight fires was therefore a major issue. Borgonyà was a pioneer in many aspects, and this field was one of them. The fire department was created right from the early days of the community. In 1909 it comprised 10 firefighters and 8 auxiliary members. All those involved combined their tasks with their jobs in the factory and were prepared and equipped for emergencies.

First-aid Kit

1930s. Provenance: Borgonyà Sports Club

More than 2,000 km from their native Scotland, the Coats family built a small town and one that at the time, just had to have a football team. The company kitted the team out in their home town’s club colours, the black and white of Paisley’s Saint Mirren Football Club. These were to be the regional origins of a sport that would eventually take a firm hold in Osona.

Borgonyà's current football field was inaugurated in 1924. However before then matches had been played on a football field close to the factory. These matches on the pitch were the first ones played in Catalonia in 1895 between two teams from different towns; the Sociedad de Foot-ball de Barcelona, the forerunners of what was to become FC Barcelona in 1899, and the Associació de Torelló, which was made up entirely of British and workers in the industrial community being built. The chronicle of this double contest was published in the newspaper El Diluvio.

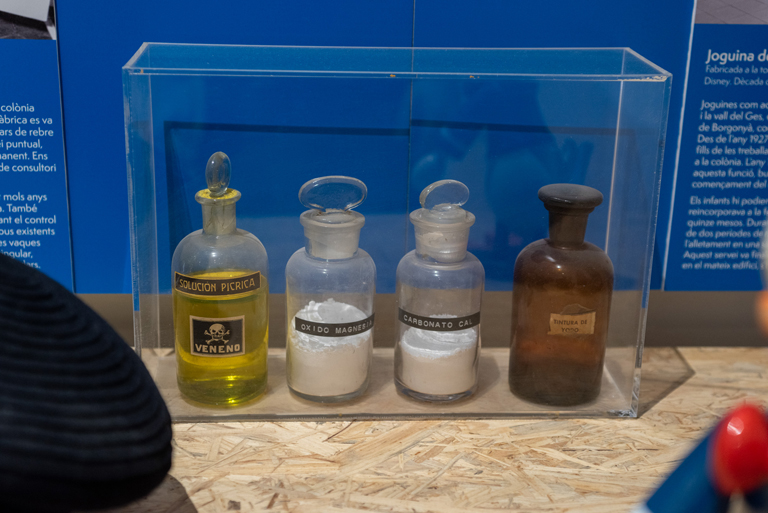

Medical Equipment

1950s. Provenance: The Guri-Casamira Family

One of the most appreciated and distinctive services of the industrial community was the medical centre. The chance to receive medical cover was offered to all the settlement’s workers and their family members soon after the creation of the factory. This was not a one-off service in Borgonyà, as was the case in most industrial communities, but a permanent fixture. The area where you are now was used as a doctor's surgery and home for many years.

The community also provided other health services. It had its own pharmacy for many years. The health of its inhabitants was also cared for with the performance of regular checks and analyses of the water in the community’s numerous wells, as well as the milk from local farms. Another unique service, that of the settlement’s slaughterhouse, was also subject to scheduled hygiene monitoring procedures.

Disney-licensed Donald Duck Toy

Manufactured at the Vila Soldevila woodturning company from Torelló. 1950s. Provenance: The Turnery Museum from Torelló

Toys like this, which were manufactured in the woodturning companies from Torelló and the River Ges valley, were to be found in the early nursery at Borgonyà, and which was popularly known as the ‘cradle house’. From 1927 onwards the company offered this service for the workers’ children, giving preference to resident families in the community. In 1952, a new building was made for this service, in a larger, sunnier space, at the beginning of Carrer Girona (Girona Street).

Children were able to enter the nursery as soon as their mothers returned to work, and they could stay there until they were fifteen months old. During this stay, the mothers had two half-hour periods during the working day to breastfeed them in a room that was specially-adapted for this purpose. The provision of this service ended in 1982 and a home for the elderly was set up in the same building shortly afterwards.

School uniform cap

1950s. Provenance: The Sellarès-Oró Family

School material

1960s. Provenance: The Vilà -Puigdemunt Family

The Coats arrived in Borgonyà with Scottish labourers, who trained the local workers. The Scots, who were Protestants, came with a teacher for their children. The Bishop of Vic, Josep Morgades, founded a school house in 1898 in order to avoid a potential expansion of Protestantism, it was run by Dominican sisters in order to educate the children of the community’s workers. Since then and for many years (apart from three years during the Spanish Civil War when lay teachers were employed) a priest and a teacher took care of the boy's education. The Dominicans, who were commonly-known as the ‘Sisters’, took care of the girls.

In 1969, the girls' school was closed and both the boys and the girls were taught together until the 1979-80 school year, this was the last in Borgonyà to remain under company control. The timetables were different from those of the other schools in the area, as in Borgonyà they were adapted to the factory timetables of the parents who were employees. The girls had to combine regular education with sewing classes.

Stove

Rayo brand (Spain). 1930s. Provenance: The Guri-Casamira Family

Housing was an important characteristic and one of the most valued services in Borgonyà. The first workers' houses were built in a well-defined hierarchy on Carrer Escòcia (Scotland Street). Next cam the construction of houses on Carrer Paisley (a street named after the Scottish city where the Coats family came from), Carrer Borgonyà and Carrer Coats. The oldest buildings on these streets are similar in style: they were typical terraced houses, with facades facing to the east and west, with a courtyard at the back that had a shared path. In total, each house was some 75 m2 and was of a very British appearance.

During the first part of 20th century the community underwent a phase of growth and consolidation. The construction of the homes also changed dramatically after the 1940s. The terraced housing system was abandoned and replaced by a style based on blocks of 4 homes, with two living units on the ground floor and two on the first floor. The homes also had 3 bedrooms, and were now built with an indoor lavatory. These buildings also used curved barrel, or Arabic tiles for the first time. The Carrer Barcelona and Carrer Girona on the hillside are a good example of this latter architectural style.

03

The Development of the Factory and Urban Growth in the Community

Before the construction of the industrial community, this river bend area was occupied by four farmhouses with their land. A small chapel dedicated to Our Lady of Borgonyà once stood where the church is now, and this is where the community get its name from.

The Coats acquired the water rights in 1893 and they began work on the construction of the factory and the first homes in 1894. It began working in 1895, although the industrial and residential complex kept expanding throughout the 20th century. Factories and homes were separated by the Barcelona to Puigcerdà railway line that has crossed this area since 1879. The production zone lies between the road and the river. The canal is also in this area, its flow rate of 10,000 litres per second that fed two 150 horsepower Francis turbines, as well as the 300 horsepower steam engine, the boilers, the chimney, the offices and a dining room for the workers.

Three underpasses below the railway tracks connect the industrial zone with the residential area, which is made up of groups of streets and hierarchical housing and services such as the nursery (otherwise known as the ‘cradle house’), the casino, the company store, the church, the cemetery, the gardens and many others. In 1950 Borgonyà reached a total population of 862.

04

Working at the Borgonyà Factory

At the end of the 19th century, the company J&P Coats Ltd, from Paisley (Scotland), which was already distributing its high-quality yarns to the Spanish market, decided to build its own factory in the country, and it settled on the site of Borgonyà. The first factory building was inaugurated in late 1895 and a year later it was already working at full capacity with 385 workers. In 1903, the new company, called Compañía Anónima de Hilaturas Fabra y Coats SA was established, stemming from the business association of Coats with the Catalan group SA Sucesora de Fabra y Portabella and the English Sewing Cotton Company from Britain. The new company operated in Borgonyà until the year 2000.

Fabra i Coats produced a wide variety of high quality yarns at its plants in Borgonyà, Sant Andreu (Barcelona) and elsewhere. The brands it marketed were well known and appreciated, and included Cadena, Ancora and Cometa. The production peak at the Borgonyà factory in the early 1970s recorded manufacturing rates of 80 tons of yarn per week.

A thousand people worked in Borgonyà during the years of maximum production. The majority of the employees were women, many of whom came from farms and neighbouring towns during the company’s early years, although many were to come from outside Catalonia in later years. The duration of the working week totalled 64 hours and 30 minutes, however a 48-hour week was introduced in 1919. The factory determined the pace of life in Borgonyà.

Thematic Objects – WORK

Worker’s apron

1940s. Provenance: The Comellas-Mongay Family

Worker’s shirt

1950s. Provenance: The Bujet Family

J&P Coats box and threads

Early 20th century. Provenance: The Comellas-Mongay Family

Retort roller

1970s. Provenance: Dolors Mora

In the factory the workers dressed in accordance with their roles. The supervisors and workers dressed in blue mechanics’ suits. The women's attire, as in almost the entire textile sector, was a typical blue smock. The women made up the majority of employees in the factory and amounted to around 70% of all the workers throughout the 20th century. In the preparation process, the fulling mills and polishing brushes were only worked by men. Women were predominantly employed in drafting and the use of draw frames and roving frames. At the end of the spinning process, at the spinning frames and the reeling machines they were an overwhelming majority. This central role of women in textiles has not always been recognised in all its importance and their contribution has often been either underestimated or ignored.

05

Never leaving, not even to go shopping

Borgonyà is one of the most comprehensively-planned industrial communities in Catalonia. Apart from providing housing for employees of all ranks, Fabra i Coats provided them with services that made the community unique when compared to others in the Ter basin area: a church, schools for both sexes, cooperative/economy, a workers’ mutual assistance association, a casino (a social centre with a broad ranging variety of theatre, cinema and dance options, as well as a café), a sports field (with a football field and tennis courts), a workers’ restaurant, a barber shop, a small railway station, a post office, a cemetery, a nursery school and the permanent services of a doctor and its own pharmacy. These services made Borgonyà a self-sufficient industrial town that was inspired by a paternalism that sought to control the lives of its inhabitants.

Thematic Objects – THE CO-OP STORE

Co-op store shopping trolley

1990s. Provenance: The Gálvez-Rodríguez Family

Co-op store card

1960s. Provenance: Teresa Parés

Co-op store coins

1940s. Provenance: The Archive of the Borgonyà Neighbourhood Association – Sant Vicenç de Torelló Town Council

Mirinda soft drinks box

1970s. Provenance: The Ter Museum

Scales

1960s. Provenance: The Ter Museum

Food and drink was available for purchase in the community workers’ restaurant from its very beginnings. However at the end of 1910 the cooperative store La Familiar Borgoñense was opened on Carrer Borgonyà. The 1920s were prosperous times, and apart from groceries, the cooperative also had a butcher, a herd of stock, pastures, a slaughterhouse, a barber shop, a tobacconist’s, a public telephone and its own bakery oven. The La Familiar store was closely-tied to the cooperative spirit of the times, although as a colony cooperative, it remained under the administration of the company. In 1958, it was inaugurated in a renovated form as a company store, it lost its original name and fell under the complete control of the company. It operated in this manner until 1986.

06

Social Life and Social Control

Life in the industrial community centred on the factory schedules. The siren sounded the work shifts and the bells did the same for life in the community. This was an existence where cultural, sports and leisure activities all played a significant role. Theatre, choir singing, cinema, popular festivals, walking trips, fishing and football were essential to promote an active social life among its inhabitants. Many of these activities in Borgonyà were administered by the Casino, a social centre type organisation that had been created and controlled by the company. In all events both inside and outside the casino-organised events, whatever the activity, life went on as it did everywhere else, with laughter and with tears. However in the community everything was monitored by the company, which was often represented by an administrator, who took charge of all those affairs that concerned the community. Despite this aspect of social control, strikes and labour conflicts did in fact take place in Borgonyà, although less often than in the surrounding industrial urban centres.

Thematic Objects – THE CASINO

Film can and reel

1950s. Provenance: Sant Vicenç de Torelló Town Council

Record player

Provenance: Archives of the Borgonyà Residents’ Association - Sant Vicenç de Torelló Town Council

Cinema tickets

Provenance: Archives of the Borgonyà Residents’ Association - Sant Vicenç de Torelló Town Council

Notice board of Casino activities

Provenance: Archives of the Borgonyà Residents’ Association - Sant Vicenç de Torelló Town Council

The company also facilitated leisure activities in Borgonyà. The building for the Borgonyà Recreational Centre was built in 1897. In the 1920s, the scope of its activities was expanded and a board was established for this new project which after 1924, was known as the Casino. It was designed exclusively for leisure activities and was run under company supervision. One of its statutes states "Discussions on politics and religion will not be allowed". The Casino’s premises combined a café area, which was mainly used by men for many years, with a main hall and a stage, which hosted plays, film screenings, dances and parties. The Casino also provided facilities for recreational activities, such as chess and billiards, and cultural activities, such as conferences and reading. It was severely damaged by a fire in 1977 and was subsequently managed by the Sant Vicenç de Torelló Town Council as a multi-purpose hall.

07

Borgonyà Today. Protect it and enjoy it!

Fabra i Coats, the company that ran almost every aspect of life in Borgonyà, today no longer exists in the community. However life still goes on there, and in 2022 nearly 400 residents lived in what is one of the most important sites in the Ter basin area and in Catalonia in terms of heritage. In 2013 Borgonyà was declared a Cultural Area of National Interest (BCIN) by the Catalan Government, and it is now recognised as one of the most representative industrial communities of all those that characterised Catalan industrialisation in the Llobregat and the Ter area.

The streets and buildings of Borgonyà narrate a history and a heritage that must be protected and preserved. However this heritage is both a memory and a present-day phenomenon, as this community of Scots origin, which was first founded in the late 19th century has become a living town that is proud of its history.

THE MEDICAL CENTRE

Texts for Medical Centre from Borgonyà Industrial Community.

08

The building where we are now is formed by two L-shaped terraced villas in an inverted U-shape, with a ground floor, walled on all four sides. It is known by Borgonyà residents as the medical centre. One of the small buildings, which now hosts the exhibition area, was used as the doctor's home, while the other, which we are now in, was once the colony's medical surgery.

These buildings, which appear on a plan dated 1912, were originally used for other purposes, however, during the second half of the 20th century, up to the year 2000, shortly before the factory closed, it was dedicated to healthcare.

The door we use today to enter the doctor's surgery was once the back door. It was used for medical emergencies, often accidents at work. It was also meant for employees during the working day and used to avoid long waits that affected factory production. Those patients who could not walk were carried in on a wheeled stretcher that could only go as far as the entrance, as it did not fit through the door. This stretcher is today an exhibit in the infirmary.

09

The doctor was a prominent figure in the community. Medical care was available to employees from the factory’s launch in 1895. In the early years, Dr. Medir, who did not live in the colony, was responsible for visiting the workers, especially when accidents occurred at the factory. Over the years and with increasing worker numbers, the company became concerned about excessive patient waiting times after minor accidents and the decision was made to take on a resident doctor. In 1920 Dr. Mateu was hired. A few weeks later Dr. Querol was provided facilities in the complex known as the pharmacy. This building no longer exists, however it stood near the football pitch and was similar to the medical centre that still stands today. A succession of doctors, Monmany, Clariana, Raureda and Latorre preceded Doctor Joan Aranda, who arrived in Borgonyà with his family in 1956. He practiced and resided there until 1974, when he was replaced by Doctor Mullor, who did not live in the community.

10

Nurses in many cases were responsible for applying and administering medical treatment. The knowledge and skills required for their job was combined with discipline and thoroughness in the administration of medical reports and all other necessary paperwork. The ability to listen and to exercise discretion when attending to patients was also part of their everyday lives.

The working day was shared between three nurses. While one did the morning shift, from 6 am to 2 pm, their colleague did the afternoon shift, from 2 pm to 10 pm. The night hours were covered by a trainee. Among these women were Ramona Casamira, a nurse and midwife who began her work her in 1953, helping with the births of many residents. Shortly after finishing her nursing studies, Consol Bou worked here from 1969 to 1985. Other nurses who also passed through the Borgonyà practice included Teresa Riera and Dolors Català, and trainee Pancracio Cucurella. Before them, and despite not being trained nurses, Mònica Agustí, Lucinda Pérez and Esteve Portero also took care of the patients.

11

The Waiting Room

Waiting is generally the first thing we have to do when we go to the doctor. And the community’s residents were no different, they walked in, through the door, which had been open since early morning, to enter the waiting room. There were about twenty wooden chairs along the wall, a rather decorative fireplace, and a central table which from the 1960s offered the newspaper Gaceta Ilustrada and ¡Hola! magazine.

Patients needed to request a visit and the system worked on a strict first-come, first-served basis. When one patient left the doctor's office, the next one entered. In urgent cases patients could go directly to the rear of the surgery and see the nurse. Due to the high number of residents in the community, the waiting area was extended with chairs placed in the corridor.

12

The Doctor's Office

The doctor received patients in this office. This room had a table, with the doctor's chair on one side and two for the patients on the other. An eye chart to test vision hung on the wall. The main piece of furniture was the bed, where the doctor examined the patients. A lot of filing cabinets, like the one in the room today, housed the medical records of all the workers who passed through the factory.

13

X-ray Room

Records show that the equipment in the doctor's office was modernised in 1951, with the acquisition of an X-ray machine being of note. The use of the two changing rooms next to the office aided the optimisation of the machine, speeding up the process and reducing the loss of working hours. The doctor was in charge of showing the results to the patients and, if there were doubts, they were given a plate that was revealed in the dark room next to the window. Every year, all the workers in the factory had their lungs checked by the machine.

The wall facing the waiting room was protected by panels to prevent the spread of radiation.

14

The Nursing Room

Direct access to this room was available for workers who had been injured in factory accidents. The staff were alerted by a bell and patients went straight into the infirmary. Two beds, a sink, a medical autoclave, a medicine cabinet and the nurse's table, with four chairs, comprised all the furniture in the room. This was where the nurses filled out prescriptions, sterilised gauzes, ordered medicines and carried out the wide range of tasks required in the everyday work at the medical centre, however their main responsibility was to emergency care.

In 1973, at the height of maximum employment in the factory, 986 people worked at Borgonyà, and about twenty accidents occurred every day. Most of the accidents involved injuries to the limbs from the machinery, especially in the carders, however eyes injuries also occurred as well as accidents with thread, which wound around the fingers and cut into them, as well as wounds from splinters.

15

Treatment Room

After visiting the doctor, and when necessary, patients went to the treatment room where the nurses would take care of their needs. This room had a set of scales for adults, with a height metre, and another for babies, there was a bed in the middle, a sink at the back and a cupboard unit where all the utensils and medicines were meticulously stored. The equipment of a well-stocked clinical laboratory was stored on top of one of the cabinets.

This room was used by the nurses to carry out analyses, blood pressure checks, treatments and where they administered medicine. They also cared for many babies and performed gynaecological examinations on the workers. Nonetheless, when it came to pregnancies, the patients were referred to the community midwife, who was responsible for monitoring their progress until the baby was delivered, and which, as long as there were no complications, took place at home.

16

This was the main access door to the surgery that was staffed during the entire week by healthcare professionals. The door opened at 8 am, although the nurses were there from 6 am, and it closed at 10 pm. This entrance was used by the residents of the community to access the doctor's office when they were working at the factory.